Additional excavations were conducted in March and April 2017 to gather important archaeological data prior to potential site impacts. Fieldwork included the systematic excavation of test pits and test squares using shovels and trowels, with soils passed through narrow mesh screens to recover artifacts.

These hand excavations were followed by mechanical (backhoe) stripping of topsoil to search for cultural features (i.e., soil stains or structural remains) representing evidence of site occupation. These investigations exposed three cultural features and recovered over 1,900 historic-period artifacts.

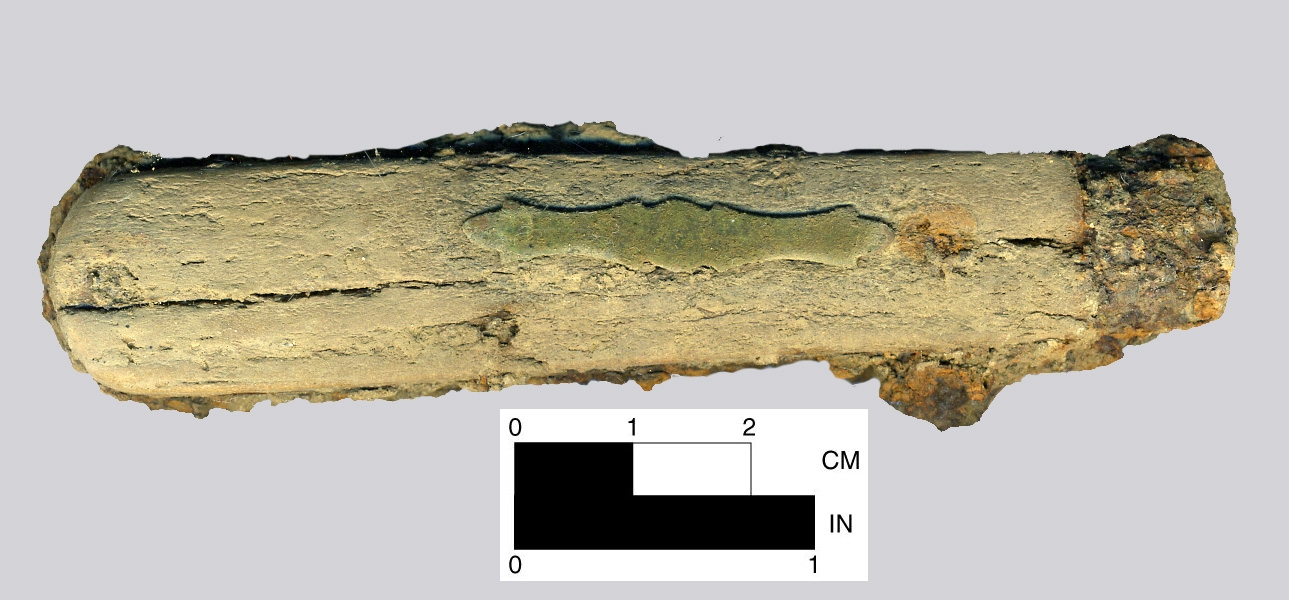

The three cultural features included the previously-identified collapsed chimney remains—the only architectural feature found at the site, as well as two ash and charcoal lenses—one representing the underlying base of the hearth (fire box) and one interpreted as a nearby episode of chimney clean-out. The chimney remains mark the location of the former farmhouse.

This feature consists of a concentration of flagstones made of limestone. The flagstones do not appear to be in intact courses, suggesting that the chimney may have collapsed slowly over time rather than all at once.

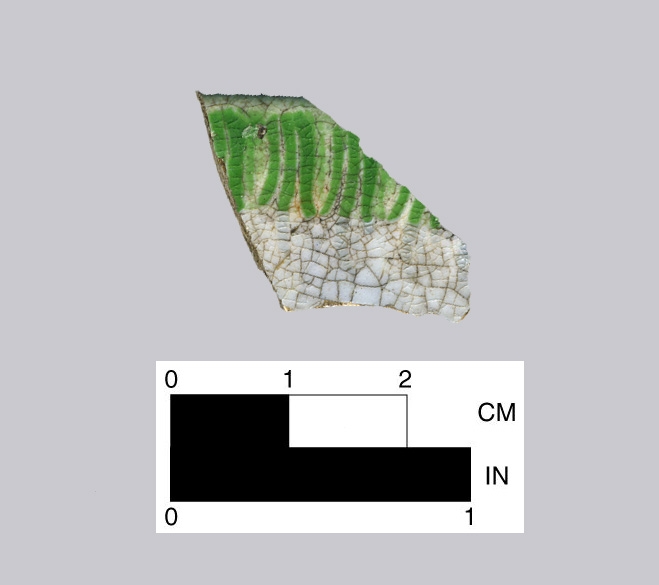

Excavations produced over 1,900 historic-period artifacts (a relatively small number for such a site), with most consisting of small, fragmentary specimens. (Each individual fragment of material that provides evidence of human use is considered an artifact during the investigation.) The bulk of the artifacts were found in the vicinity of the former farmhouse, with a smaller concentration occurring near a barbed wire fence east of the structure. The recovered artifacts consisted largely of kitchen-related items and architectural debris, typical for farmstead sites. The kitchen artifacts included broken pieces of ceramic dishes and crocks (called “sherds”), fragments of glass bottles and jars, and a few utensil parts.

Architectural debris included nails and small amounts of mortar, brick, and window glass. The remainder of the items included pharmaceutical bottles, lamp glass, buttons, a glass bead, belt buckle, porcelain doll fragments, shotgun shell, pocket knife, and stoneware smoking pipe fragments.

All recovered artifacts have been analyzed and are curated at the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology in Lexington, KY.

To learn more about this project and other related topics, check out “Archaeological Investigation of the Bain-Cline Site,” developed by GAI Consultants, in the Classroom Materials tab.